Reverend Clergy, Distinguished Guests, Friends:

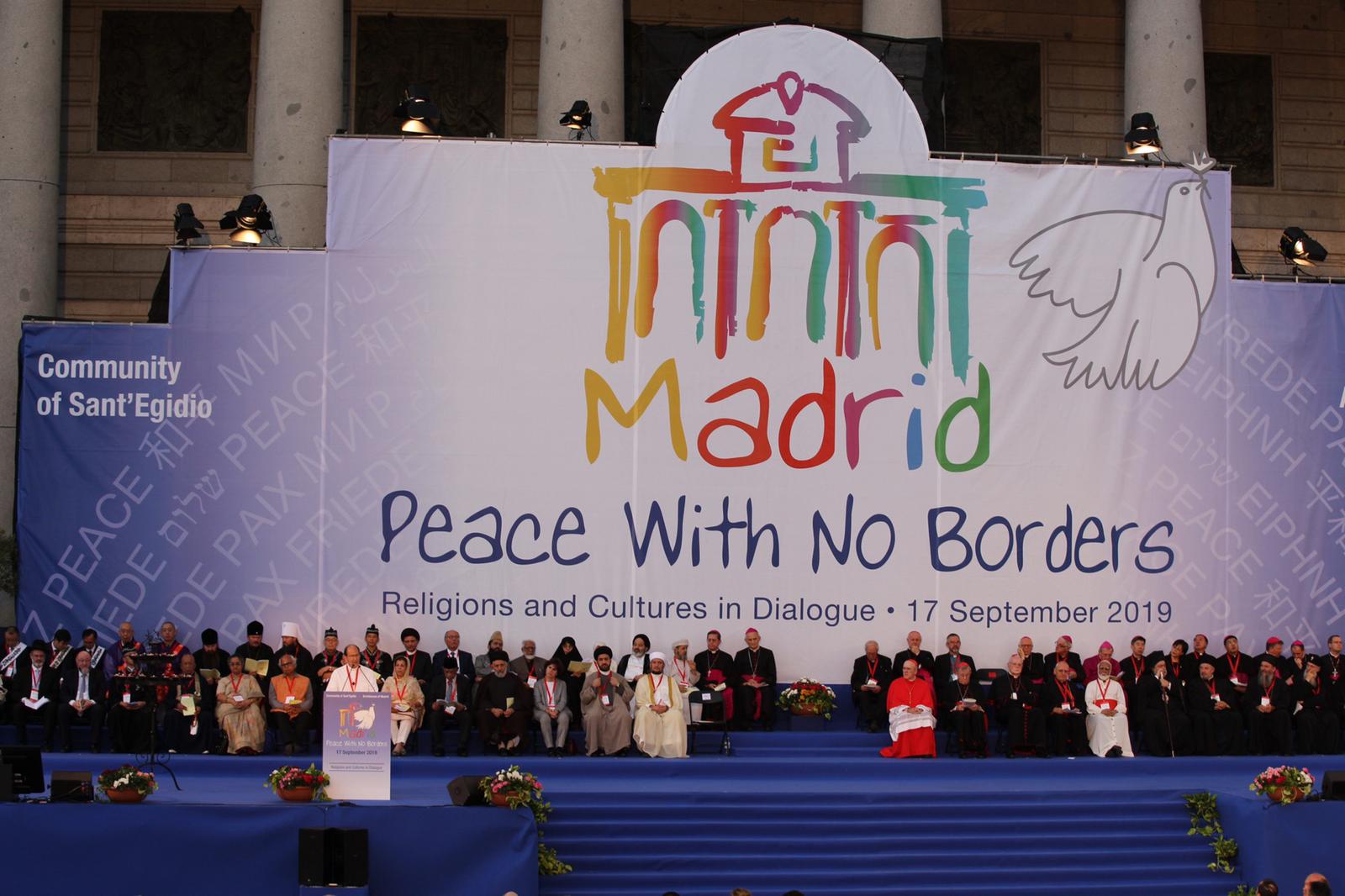

I want to express my gratitude to the Community of San Egidio for organizing this important conferance here in Madrid. And I am honored for the opportunity to address this gathering today. I speak to you today as a lifelong servant of the Armenian Church, who has labored for my people in Europe, the Middle East, America, and our homeland of Armenia.

Armenians are widely dispersed across the globe, and there are many historical reasons for that dating back to antiquity. But the pre-eminent cause of our dispersal came just over a century ago, when the Ottoman Empire targeted its Armenian citizens for mass extinction and exile, in the tragic episode that came to be known as the Armenian Genocide.

Unfortunately the same catastrophe would later be visited upon other people. A century ago, the world drew no lesson from the suffering of the Armenian people. As a result, other people—Jews, Cambodians, Rwandans, and others—have suffered the plague of genocide in the hundred years that followed. Right down to the present day.

This is why the subject of this panel—the Prevention of Genocide—is so close to my heart. The entire world acknowledges that genocide is the greatest crime imaginable. And yet somehow, genocides keep happening—and the world seems uncapable of responding to it, let alone preventing it. How can that be?

I said that this subject is close to my heart, and indeed my interest is very personal—because genocide had a deep effect on the story of my family. With your permission, I would like to share that story with you today. It is the story of my paternal grandmother.

It was she who instilled faith in Christ into our hearts—first in my father, later in my brother and myself. As a boy, I took the love and piety of my grandmother for granted. But when I reached a certain level of maturity and under¬standing, I realized what a remarkable woman my grandmother truly was.

She had been a young bride, three months pregnant, when the soldiers arrived to take her husband away, never to return. My grandfather was fated to be one of the countless martyrs of the Armenian Genocide. Imagine being a young girl, in a world where suddenly your very identity is a crime. Imagine having your dreams for a happy, peaceful future destroyed. Imagine being in the delicate state of childbearing while the world around you goes up in flames.

But in spite of the horrors around her, my grandmother refused to allow the door of life to close on her. She called on something greater than human courage to endure those days. Many years later, she was still clear about what that “something” was. It was her profound faith ; her conviction that God had some purpose for her. With such faith, she survived the massacres, gave birth to my father, and took care of her elderly in-laws.

My grandmother had a pain but she never demonstrated the feeling of hate. She became inspiration for me and her spirit has been guiding me throughout my ministery. In my ministery as a priest of the Armenian Church I have been commited to bring healing between Armenians and Turkes. I belive that it is important to bring healing among peopels and nations in order to prevant genocides repeting again.

Another important step in genocide prevention must be the simple act of MEMORY. We must remember that genocide has happened—and can happen again. We must remember the people who suffered under it, learn their names and their individual stories. We must remember, and never forget.

Forgetfullness is the great facilitator of evil in this world. The fog of ignorance gives evil people an opportunity to act—it encourages them into thinking they will go unpunished. The supreme evidence for this comes in the following quote, which is burned into the consciousness of every Armenian. It goes: “After all, who today remembers the extermination of the Armenians?”

The speaker, of course, was Adolph Hitler. He uttered those terrible words on the eve of the Nazi invasion of Poland; and their spirit would eventually lead to his order to extirminate Europe’s Jews in the Holocaust. The human tendancy to forget is what gave Hitler the confidence to go forward with his genocide.

What is the antidote to forgetting? Surely it is EDUCATION—which I see as a further step in genocide prevention. Education is the way individual memories are extended into the world—and into future generations. Education often comes through offical academic channels, like a required university course or a school curriculem. But it also can be transmitted through cultural forms: through the arts, books, film, music. Because of their personal nature, these cultural efforts are often more compelling—and can relate a deeper truth—than purely academic matters of fact and history.

Obviously, both are needed, and work hand-in-hand. However, I sometimes feel that educational efforts about genocide rely too heavily on political questions: on assigning blame, or trying to vindicate a case for recognition and reparations. These are very important questions, certainly. But they are parochial matters that, in my experience, draw our attention away from the larger, universal issues of genocide: involving morality, human rights, and the social conditions under which it can occur. If our goal is the prevention of genocide, and not simply its study as history, then these larger questions must stand at the center of our educational efforts.

With prevention as our goal, we need a way to recognize genocide in its early, and even formative, stages. That goes to the question of DEFINITION: How do you define “genocide”? I want to note that while mass extermination is a very old story in human history, it is only in the last seven decades that the crime of genocide has been described in a definitive way, thanks to the 20th-century legal scholar Raphael Lemkin. It was Lemkin who originated the term “genocide.” His work, based on his experience of the Holocaust and his study of the Armenian massacres, resulted in the 1948 Genocide Convention issued by the United Nations. Let me share it with you now.

The U.N. defines “Genocide” as: “Any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group, such as: (a) killing members of the group, (b) causing serious bodily harm to members of the group, (c) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part, (d) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group, and (e) forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

This definition is an important weapon in the effort to prevent genocide, in part because it gives us clear danger signals—warning signs—to look for in the early stages of an attempted mass extermination. Several provisions do not involve outright killing, but the inflicting of conditions that will inevitably lead to mass death. It is vitally important for political authorities, and moral “watchdog” organizations, to be instantly attentive when such conditions arise anywhere in the world. Generally, when you see signs of gross dehumanization of one population by another, that must be taken as a sign that a genocide is in contemplation.

My final observation about preventing genocide concerns the role of religious authorities. Needless to say, the idea of genocide is totally contrary to Christian teaching, and is also forbidden in other religious traditions. But sadly, inflaming religious passions has frequently been a method used by evil actors who wish to perpetrate mass violence.

This places a heavy burden on religious leaders, I feel. Religious leaders must never allow themselves to be used in this way. More importantly, they must use the authority they have to DEFUSE TENSIONS when these are in danger of reaching a crisis point. This should involve reaching across inter-religious divides, where leaders from different faiths come together—as a matter of everyday routine—to model harmonious, peaceful, and respectful behavior for their followers.

In my ministry, I have seen the positive effects of such efforts. For many years I have been serving on the board of the Appeal of Conscience Foundation: a group founded by a rabbi who survived the Holocaust, to bring religious leaders together in moments of potential conflict. And supporting the “Freedom of Conscience” in different societies. What I learned from my experiences with the group was that religious leaders in conflicted societies are often very isolated from each other.

I recall being part of a meeting in Viena on March 1999, when we gathered the leaders of the three native religious groups—Orthodox, Catholic, and Muslim—for a conference. During the luncheon break, the three religious leaders from Kosovo (Muslim, Catholic and Orthodox) were seating on the same table. They were having a nice conversation together and even laughing togheter . We were surprised to learn from the leaders themselves that they had never had the opportunity to site together before. They had been isolated from each other. But we felt encouraged when they responded positively to the meeting, and to each other and signed a common decleration, where three of them toghether said “Withouth forgething our sorrows, we want to emphasize to our faithful and all others in Kosovo that the history is recounting the past. No one can change the immutable past. But the future is with our power to influnce and direct. In the name of our faithful, we can demand an end to the suffering that has plagued our peopels for so long and call to look forward, to change the present era of confrontation to one of cooperation”.

I have witnessed a similar effect among my own countrymen. Several times in the last 30 years, the simmering conflict involving Armenia and its Islamic neighbor Azerbaijan has threatened to boil over. But on several of those occasions, Christian leaders from Armenia and Muslim leaders from Azerbaijan have successfully defused tensions by appearing together in public, denouncing violence, and modeling an attitude of tolerance for each other.

Such outward examples of mutual respect, friendship, and recognition can project to the public that a different relationship—one not based on aggression and violence—is possible. That helps move the public in a positive direction, away from fanaticism and towards tolerance. The lesson is that when religious leaders find common ground, and come together across inter-religious divides, they can intervene in dangerous situations and have real success in averting violence.

Of course, none of the things I’ve mentioned can guarantee that violence will be averted. Preventing genocide is a monumental task that is not easily undertaken. But we also have a monumental moral imperative, to use whatever tools we have to prevent genocide, in any way we can. The tools I have mentioned—Memory, Education, a strong Definition of genocide as a crime, and the potential to Defuse Religious Tensions—do not require mighty armies and powerful nations in order to be effective. They are available to all of us, and require only our urgent willingness to put them into effect.

As people of faith, and servants of God, we are certainly compelled to take up this challenge.

Thank you.