David Rosen

Rabbiner, Sonderberater des Hauses der abrahamitischen Familie (AFH) von Abu Dhabi, Israelbiografie

If killing one person diminishes the Divine presence in the world; the extermination of wholescale communities is surely the ultimate desecration of the Divine.

Obviously, it is the sacred duty of religions and their adherents to do their utmost to prevent such terrible desecration of the Divine Presence, and to affirm the sanctity of human life created in the Divine Image.

The impact of the Shoah, the Nazi Holocaust, led to a body of international law to punish perpetrators of genocide and try to prevent such atrocities, and using religious networks to raise awareness and assist enforcement in this regard is of course of great importance.

Ultimately however, the challenge is an educational one, in which Religions have a critical if not unique role to play, through instilling a true reverence for the sanctity of human life and dignity. In addition, there is the role of memory. While memory plays a critical role in all religious traditions, it is memoria futura, the impact of memories on our consciousness and our consciences in the present and future, that is the paramount concern and goal. e

It is accordingly of critical importance that younger generations learn the lessons of such tragedies in order to be more alert to their prevention. Yet, studies show that the vast majority of young people today are stunningly ignorant of these events.

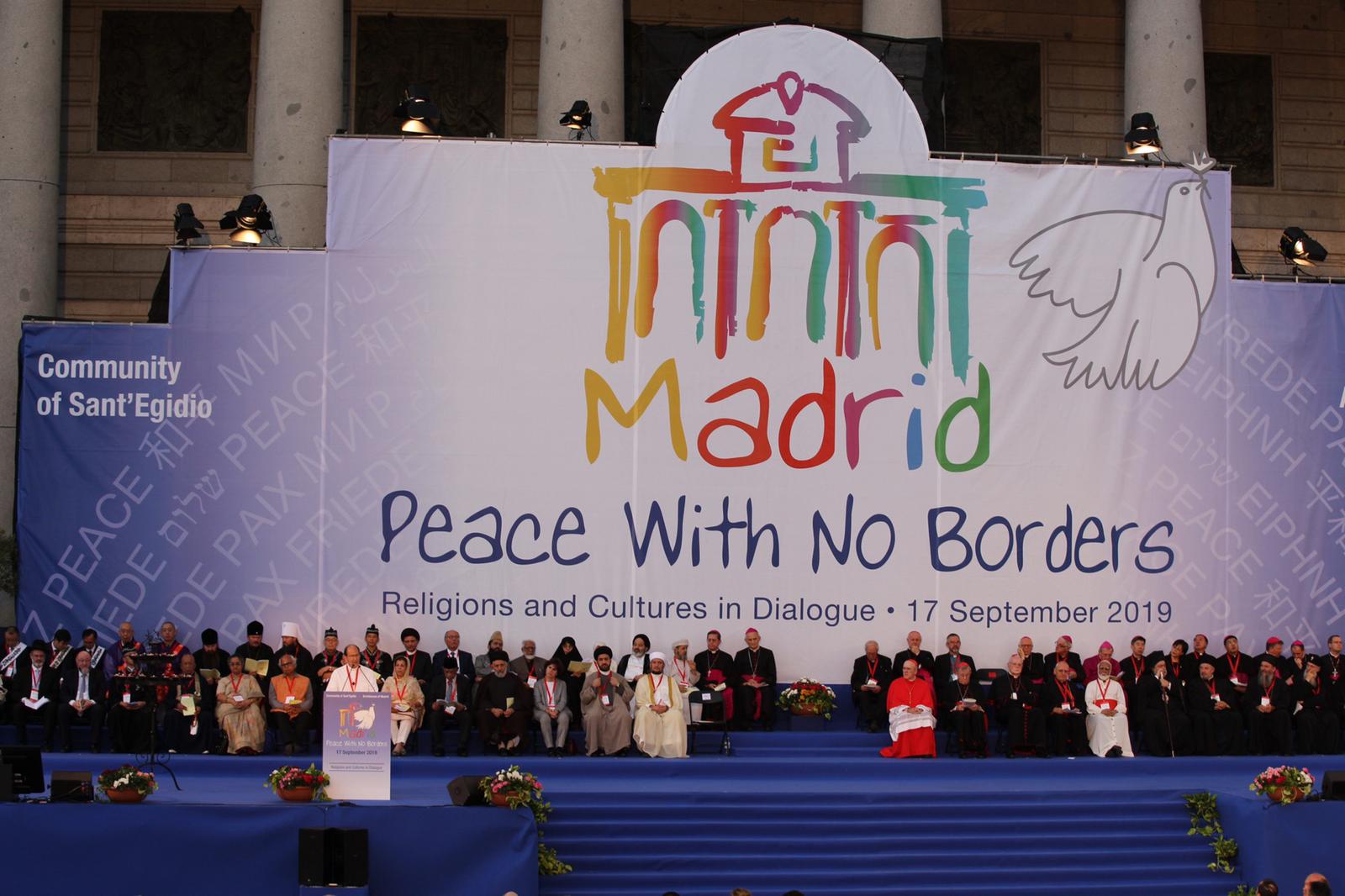

In addressing this challenge, the Community of Sant Egidio has led the way, taking young people to the sites of the Nazi Holocaust to both pay tribute to the victims but above all to learn the lessons of the tragedy.

But other than the horror of it all, what are the lessons of such tragic genocides?

Recently Cardinal Blaise Cupich has addressed this subject referring to William Dodd, an American historian from the University of Chicago who was chosen by President Roosevelt to be America’s first ambassador to Nazi Germany. Initially hopeful and encouraged by the spirit of the “New Germany” that emerged from the ashes of the first World War; as Hitler’s rise to power led to the increasing persecution of Jews and others, Dodd’s excitement turned to fear.

He telegraphed the State Department firsthand accounts of attacks on Jews, the censorship of the press and the enactment of new laws that restricted the rights of the Jewish people and other minorities. However, his superiors treated his communiques with indifference and his reports were considered too sensational to be reliable.

Dodd noted that Hitler’s rise to power and the policies that led to the Holocaust developed through stages. First came the bigoted language targeting a minority. Initially dismissed by society as “only words” and marginal, these became increasingly widespread, credible and even “respectable”. The next stage involved targeting the “other” as a scapegoat for the grievances people were told they should have, especially as they reflected on their experience of loss from the first World War. Thus, hatred became a political tool for cohesion and empowerment leading to the dehumanization of “the other”; which in turn led to the intent and action of extermination.

While our world today is significantly different for that of Germany in the 1930s, there are dangerous echoes of such bigotry, prejudice, and stereotyping in our contemporary society that must ring alarm bells for every person of conscience.

Ignorance of the past condemns us to repeat it, said George Santayana. Thus, the need for Holocaust education in schools is of the utmost importance. And it not only the Nazi Holocaust that must serve us as a burning warning, but also other genocides in recent times. The slogan “never again” demands of us to keep alive the memory of the genocide of the Armenians and other Christian communities under Turkish rule in the early 20th century; and the genocide of Bosnian Muslims at Srebrenica and elsewhere; as well as the massacres in Rwanda at the end of that bloody century, and more recently the extermination of Yazidis in particular at the hands of ISIS.

However even worse than ignorance is denial.

Why people seek to deny these horrendous events, is itself something of a puzzle. Often of course it stems from a deeply guilty conscience and thus a desire to minimize the extent and significance of these atrocities. The Israeli historian of the Holocaust Yehuda Bauer states it succinctly: “The denial of the Holocaust is due to the inability of a society to accept what it did.” This of course is especially the case concerning genocide deniers from the communities that perpetrated these atrocities.

Often racism and prejudice are themselves the motives. In addition,conspiracy theories have their attraction in which, as mentioned in the case of Nazi Germany, the victim can be portrayed as the scheming manipulator and a convenient scapegoat for one’s own ills.

The danger of denial of genocide has been described by the former Grand Mufti of Bosnia Dr. Mustafa Ceric as not only “a denial of the truth about real physical Genocide… that continues the real psychological genocide against the victims of genocide; (but also) a justification for potential new genocide because everyone who denies the real evil of genocide, is ready to perpetrate that evil again”.

He notes that in today’s world “voices of anti-Islamism and anti-Semitism are getting louder and louder, (which demands that we) raise together our voices against this plague. Obviously (he declares) the cry „Never Again" has not been loud and consistent enough”.

This demands of us not only to combat the denial of genocide, but to do our utmost to combat the mindset that can allow genocide to happen. It demands that we condemn any denial of human dignity, stereotyping and bigotry. For words might not kill in themselves, but they can certainly lead to such. As it is written in the book of Proverbs 18:21,“life and death are in the power of the tongue”.

And we must be ever mindful of the famous words of the Lutheran pastor Martin Niemöller :

“First they came for the communists, and I did not speak out — because I was not a communist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out — because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out — because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me — and there was no one left to speak for me.”

To speak out against all bigotry and inhumanity is our duty, to prevent such terrible genocidal atrocities; and it is people of faith, of religion, who have the greatest obligation in this regard.