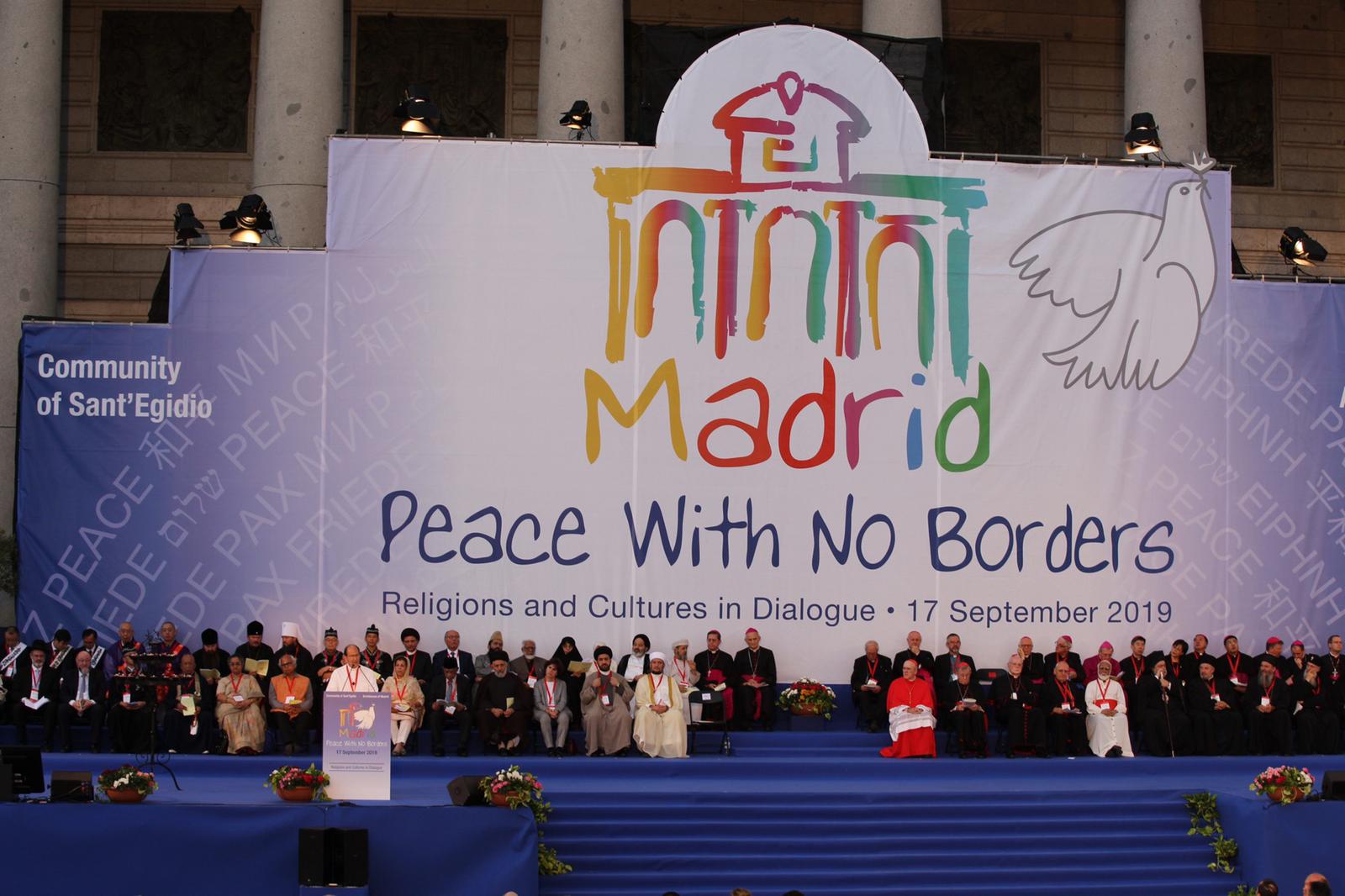

Once again, I’m delighted to participate in the annual meeting of Sant’Egidio, a movement for which I have tremendous respect and admiration – both for its devoted members and for its activities to advance peace in the world.

When I was asked to speak on this panel – Women and Peace –two questions came to mind: ‘Why is there a need for a session on ‘Women and Peace?’ Would anybody think of holding a panel on ‘Men and Peace’? Secondly, I wondered why my distinguished co-panelists were all female. Is this simply a ‘women’s issue’ for us to discuss amongst ourselves?

To answer my own first question, it is clear that there is still a need to shine a light on the role of women as peacemakers and the crucial importance of ensuring that they have a place at the peacemaking table - at the community, national and international levels. Even in this day and age, we see that women are not naturally included in discussions to advance peace as a norm. If it was ‘natural’, women would be present at the table simply by virtue of the fact that they are 50% of the population and equal members of society. It still cannot be called ‘the norm’ if we need to be ‘intentional’ about including them in peace discussions.

Even more so is this true of religious frameworks, which in the main are based on patriarchal traditions sourced in ancient cultures. In these traditions, where men hold positions of authority and are privileged over women who are generally excluded from the public domain, it’s even harder for women to take on leadership roles and amplify their voices for peace.

I am not saying that women are ‘natural peacemakers’ although the role they have played in building and sustaining relationships within families and communities for thousands of years has certainly honed their skills. I’m also not saying that all women are peacemakers. God knows we’ve experienced many around the world who are not!

But the feminine characteristics, and let me stress that they are found in both men and women, that privilege caring, compassion, mediation and dialogue over the more masculine traits of strength, dominance, assertiveness and competition, need to play a more prominent role in our peacemaking – and the easiest way to make that happen is to nurture more women as public leaders in this area. We also need to find and encourage the male champions who will support female leaders in this role. These feminine characteristics are the basis for alternative models of leadership that are not normally predominant in our world and, quite frankly, are sorely needed given the parlous state we live in.

Simply put, we cannot afford to exclude women from peacebuilding.

Studies from UN Women show that when women are involved in peace processes, sustainability of that peace over 2 years is 20% more likely and 35% more likely over 15 years. And yet less than 4% of signatories to peace agreements are women and only 10% of negotiators are women.

So to answer my second question – is this only a women’s issue for us to discuss amongst ourselves? …absolutely not if we are truly committed to reducing violent conflict and advancing peace in the world. Men must be part of this conversation too and champion the role of women. As the late Kofi Annan once said, “the single best ingredient for peace is women.” He was instrumental in implementing the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security, which among other recommendations, encouraged women’s participation in peace-making.

During the time I have left in this presentation, I’d like to share some insights from a fascinating project I’ve been directing in Israel over the past few years, with highly influential religious actors, male and female, Jewish and Muslim.

The overall purpose of the project is to expand constituencies of peace among deeply religious communities who are generally perceived as stumbling blocks to a negotiated peace agreement of the Arab-Israeli conflict. In this project we focus on how religious leaders can be part of the solution and not the problem.

The participants discuss holy texts that can shed light on the core issues of the conflict. Through listening and learning from one another within their intra-religious groups, and then with those from the other faith, the leaders develop a ‘religious language’ which forms the basis for recommendations on how to advance peace politically. The leaders also implement practical activities to expand peace in their communities.

However, rather than talk about the general activities of the initiative, I want to focus here on what became one of our biggest unanticipated challenges –gender tensions – that almost blew up the project. One of the guiding principles of the organization I represent, Search for Common Ground, is the principle of inclusion. We find that including a wide variety of views is an effective way to advance positive change. So, we aimed to recruit equal numbers of men and women.

But as the Muslim group leader said there were almost no female Muslim religious leaders we recruited instead deeply religious women who were leaders in other fields – education, social work, law.

Fortunately, we had no problem recruiting female Jewish leaders; heads of women’s religious seminars, university departments, and the like. But this did lead to differing levels of religious knowledge between the sides.

There were various altercations during the project that heightened the gender tensions, but the crux came when the Muslim and Jewish women wanted to hold meetings about sacred texts without the men present. Our male group leaders were very suspicious and objected to a perceived ‘feminist agenda’. They insisted on knowing what was being discussed. They refused to ‘allow’ the women to hold separate meetings without being present to ‘supervise’. Rather than battle this head-on, which threatened the continuation of the project, we came to a compromise whereby the two male group leaders could attend the meetings but as observers only.

After the first meeting the men no longer came to the meetings – their fears were allayed. They saw that the women were not ‘plotting to take over’! They simply wanted the intimacy and the opportunity to discuss the texts in a way that might not have happened in a mixed gender meeting. The Muslim and Jewish women in general proved to be the most committed participants in the project and are highly influential in promoting peace in their communities.

In conclusion here are 3 lessons we learnt about the inclusion of women in religious peacebuilding from this project:

Flexibility is needed in recruiting women. Sometimes you will not find female religious leaders, but if you cast your net more widely, you will find others who can take their place and ‘learn on the job.’

Sensitivity – including women on an equal footing with men may be seen as threatening traditional societal/religious structures and norms which results in ‘push-back’. The solution is to create an empowering experience for both women and men, and be sensitive to the fears on both sides e.g. women’s lack of confidence and formal religious knowledge as well as men’s loss of power and privilege.

Adaptability is a crucial ingredient in this field of religion and peacebuilding. Despite necessary planning, more often than not, we have to adapt according to need – all the more so when women are an integral part of the plan.

If you are wondering what is the difference between flexibility and adaptability, the former is needed for growth, the latter for survival. Hopefully our societies, including our religions, learn to adapt more quickly to the essential role of women in peacebuilding. Our survival may depend on it.